Drawings and Objects

BETWEEN THE TRACE AND THE GESTURE

This mutual entanglement of art and life, their encroachment upon each other, the blurring of boundaries without violating them, and at the same time existing beside them – these aspects most of all characterise the work of Roland Schefferski. His arrangements, irrespective of whether they are works like A Room, Regained from Memory or Berliner Room, will always be, from one side, a constant examination of the concepts and essence of art, while from the other a form of search for a space for art – not cultivated, not ”paved” by the artist’s hand, but its ”natural” – one could say – context, which is closer to life and the everyday than galleries and museums.

The anonymity written into the title of the realisation A Room forms a sharp dissonance between the privacy of it’s the women who is its owner and her world, but it is also a code allowing us to read artistic thoughts behind the work of the artist; on the one hand it indicates something beyond art, something which art draws into its own area, on the other hand it asks a question about art itself, about its essence and force. One could get the impression that Schefferski’s works, through their aesthetics, stand on the border between art and life. But it is only when we look into them that we realise that the artist, asking himself this type of question, is looking for the answers, paradoxically it may seem, in Lebenswelt, an area which until now art had tried in various ways, most often with the impetus appropriate to the avant-garde, to force. Schefferski however, has not made the mistake of his predecessors – he enters the world whole, it could be said, walking on his toes so as not to arouse the interest of life and not to irritate art itself– leaving a quiet and barely noticed trace, some scratch or crack caused by one gesture, left on the coat hanger, thrown, like in mud, photographs immersed in porcelain, characterized with the help of someone’s profile sewn on the wardrobe, being left to chance, like the light of the sun, whose shadows plays on the curtains, or the hand of a chance person interfering with the curtain, as we know, each work of art finds itself at the same time in two worlds: in real space, as an object, and in the aesthetic world, as a spiritual content, going beyond that reality. So from the point of view of traditional art, A Room, like other “rooms” arranged by Schefferski, should a form of museum office. On the other hand, transferred into the private sphere they should become “pleasant aesthetic objects”, serving a decorative function, threatened with isolation, and thus the loss of something essential. As Hannah Arendt says: Works of art enclosed in private possession cannot fully confirm their internal importance.1

This is not so however and none of these variants stands behind the idea of the artist: A Room loses nothing of its dwelling function, life still goes on in the flat. This can best be summed up in one statement: Schefferski’s work sinks into the space of life. They do not so much become its indivisible element, as the element itself becomes characterized aesthetically. Both worlds: that of our everyday life and that of aesthetics, which assumes an eliminating function, are not their own quotations – they coexist in the same place and at the same time. On the line of art and life there is no tension – there are no “sparks”.

A Room, Regained from Memory and Berliner Room – these are forms recalling to mind Dutch painting with its climate of bourgeois houses, quiet and peaceful homes transferred onto canvas. Schefferski creates paintings of installations and spatial arrangements, which perfectly show the atmosphere of everyday life. This is the world of average, common man, who lives out his own cares, and joys, whose existence here and now often becomes reduced to the memories he leaves behind: some photographs, his wardrobe – scraps of memories of him, or scraps of his memory. But there is an idea hidden behind Schefferski’s thinking – the idea of a work of art referring to a real, concrete and current life situation, which is presented in his work The Couple: Wanting to integrate my work with the environment, in this case – the interior of a home – I superimposed the contours of the couple’s silhouettes on a two-piece, solid-colour fabric curtain. The silhouettes are embroidered symmetrically on the inner edges of both parts of the curtain. The function of the object conveys the particular daily relations of the symbolic couple’s life. In the morning, the curtains are drawn to opposite sides, and the couple leave to perform their daily tasks. I the evening, they meet again at home – symbolically as well as in reality – as the curtain halves are drawn together.2

Schefferski’s work fits into narrow gap between art and life, a gap which the artist himself can feel; like a Filipino doctor sinking his hands into the flesh of his patient, Schefferski with one gesture transforms what is ordinary into the artistic, creating a space between two spheres: life and art. His work does not aim to melt one into the other, or to allow one sphere to dominate the other, but it tries to characterize both, and, in so doing, to change their quality. Art and non-artistic reality meet on the same level, as alternately the source and the carrier of meanings.3, says Bauman, as if confirming Schefferski’s effort.

That is why Schefferski sometimes seems to act like an experienced photographer, who slows down the snapshot, and in a fraction of a second record some fragment of life, some “here and now”, brought down to emotions, thoughts, reactions, sometimes builds rooms soaked through with nostalgia, or “illuminates” a shadow, drawing a line around it and with its help shows the essence of the spiritual presence of a person. This way of acting comes close to the idea of sublimation, brought up to date by Jean Francois Lyotard. The atmosphere of unexpressed presence, making the inexpressibly present, finds its confirmation in this sublimation. As Lyotard says: The inexpressible does not exist ”somewhere else”, in other words, in another time, but in that which happens. Not sooner or later, not at some time, but as the here and now it happens, and this is the picture. 4 Schefferski, trying to show in his art this unique on every occasion concrete “presence”, sends us away to something else, something which can most simply be called values, which today – in postmodernism – can only find shelter in art.

Consistency in the way of thinking artistically, exploitation of the same themes, sounding the same areas, means that one can look at Schefferski’s art like at a kind of private album, into which are ”stuck” scraps of events and emotions. Such work is the already-mentioned environment A Room, which refers to the life of the concrete person. Developing the thus understood “personal art” Schefferski encloses the privacy of people in the form of art, and in a discreet way describes their being, allowing us to recognise the mood accompanying the works, to identify with it and to discover ourselves within it. In a very strange way the artist does not invade the sphere of privacy, but rather transforms the privacy of people, allowing us – a la Gadamer – to conduct an “honest dialogue” with art.

There is however something more here, not just an attempt to enter – through art – into one’s own world, another’s world, an “Other” one, but there is also an attempt to capture it in its ephemerality; it is like trying to capture memories, which are not able to put into an album with the photographs, but all we can do is to store them in the memory. This leaning over a person, this inquiring into his world, comes close to Levinas’s thought about the Other, the “opening” to his face. In trying to find a person Schefferski “touches” him with his art, however this is understood. In this area of art the search for truth means the penetration of human desires, habits, emotions, weaknesses. Subjectivity therefore appears here in pride of place.

Schefferski’s work, which places him in Lyotard’s project of the aesthetics of the sublime, at the same time, transcends him. His spatial arrangements, in the framework of his own individuality creating” small narratives” and being them at the same time, become a kind of “micro cosmos”, which creates its own space, values, climate, senses. Admittedly according to Lyotard such works do not aspire to universalization, and do not create objective values, but they do express something, and do so within the framework of their own individuality (subjectivity). This situation allows however everything which is aesthetic to remain in the power of the individual – both the one which creates the works and the one which receives it. But creation is at the same time a process directing oneself to “somebody”. In this sense, as Lyotard suggests, the artist and the receiver are capable of communicating through the work of art, becoming equal partners in a communicative situation, in which the work has become a pure medium. The subjectivity of the artist gets through to the subjectivity of the receiver: in this way and on these grounds the work of art becomes a private experience. Schefferski’s work transcends the aesthetics of the sublime to the extent that they not only appear as a form of question about art, about the work of art, the possibility of experimenting – as Lyotard says – in the search for categories and aesthetic rules possible to be established ex post factum. The moment of transcending occurs when the artist follows the traces of art – inquires into the space of life, in order to examine the relations between art and life.

Beata Frydryczak

This text is an excerpt from the essay "Jadwiga´s Room, or Between the Trace and the Gesture (About the Art of Roland Schefferski)" originally published in: Magazyn Sztuki / Art Magazine Quarterly, no. 11 (3/96) Gdańsk, Poland

1 Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Future: Six exercises in political thought, Publisher: Fundacja Aletheia, Warsaw 1994

2 Roland Schefferski, A record of discarded reality: II. International Festival of Experimental Art and Performance, Publisher: Central Exhibition Hall-Manege, St.Petersburg 1998

3 Zygmunt Bauman, A few words about art of meaning and the meaning of art (manuscript)

4 Jean Francois Lyotard, The sublime and the Avant-Garde: The Lyotard Reader. Publisher: Andrew Benjamin, Oxford 1989

BERLINERS

The situation of post avant-garde art seems unique because it rejects everything that has accompanied it to date – apart from art – while questions that up till now have been current had lost their sense in the context of postmodernism. After the avant-garde art, only the art has remained; after the avant-garde idea, only the idea (the sublime, as Lyotard would say) – but what is left after the work of art, particularly after Duchamp’s achievements? The artistic gesture, replies Roland Schefferski.

Setting a boundary between modernism and postmodernism can occur when art transforms its way of appearing and existing in the world, and the artistic gesture once again becomes a causative activity, behind which there stands a thought, a conception, and a hard-to-define idea of art. This moment appears when there takes place a transition from the object taken from the world of life and raised to the rank of a work of art – an aesthetic object deprived of its utilitarian value and possessing an artistic value – to an object that becomes a work of art through the gesture of the artist, which is not annexed to the realm of art, but is transferred from the realm of art to the realm of external reality.

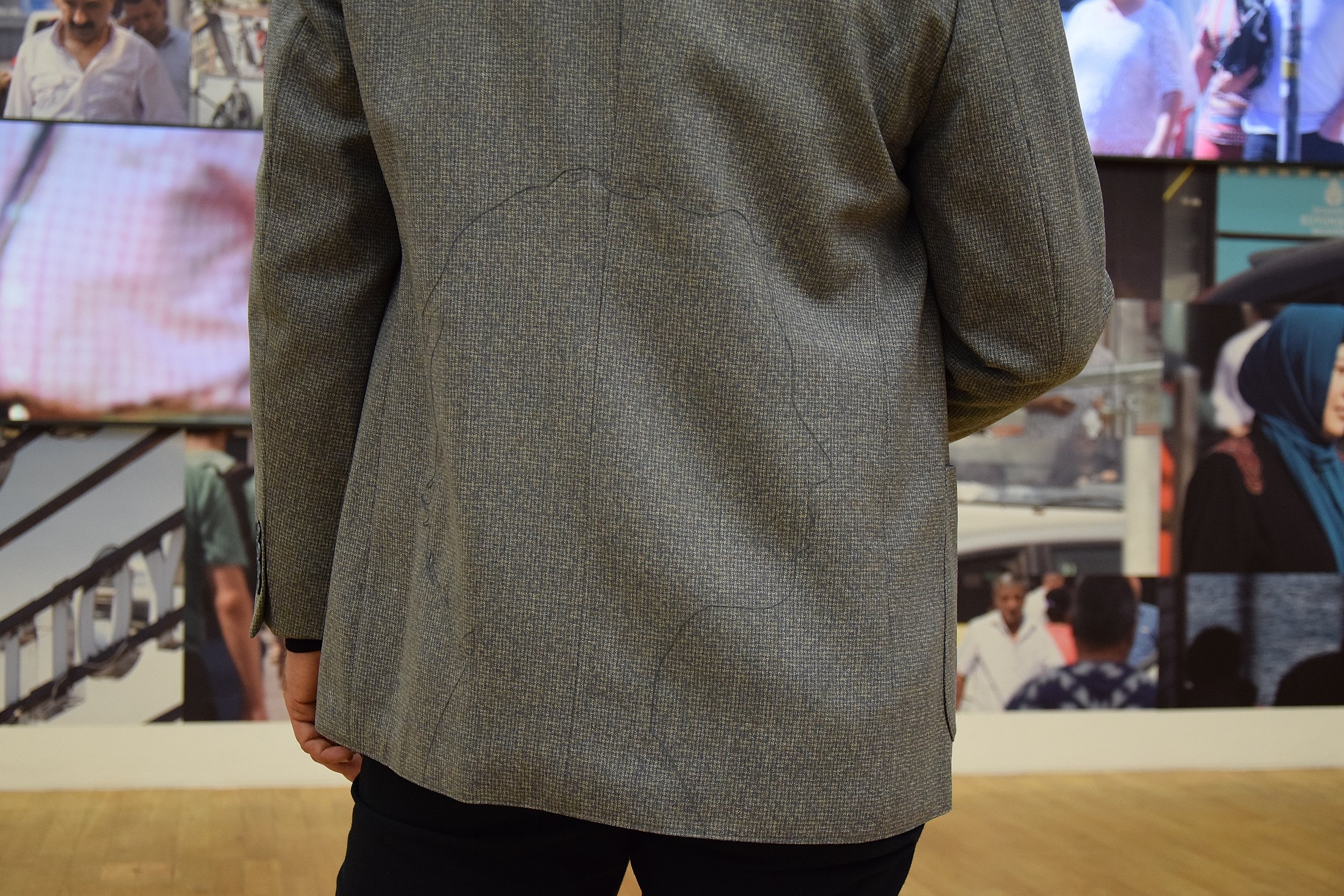

It is exactly this type of artistic activity that characterizes Roland Schefferski’s work. While putting the endurability of art to a conceptual test, Schefferski at the same time brings art to the role of a trace and the effect of the activity of artistic gesture. The artist’s oscillation between art and life takes on here the character of a battle about the idea of art, about the transfer of thinking from art as a work of art to art as an idea, which potentially resides in all things, which through the touch of an artist takes on the character of a work of art. This artistic gesture, going back to Duchamp’s first gesture, reverses – at the threshold of postmodernist art and at the end of the avant-garde – the situation, in which art gathers to itself things and objects, making museum exhibits of them. Schefferski does something completely opposite – he gives art to life, and characterizes the object by giving it back the idea or the concept of art. As he himself suggests, I am personally interested in the possibility of creating such an artistic object which does not lose its initial function. Linking in one utilitarian object and work of art, he violates neither the concept of art nor the purpose of the object. Nothing changes the object – the outline of the shadow on the jacket does not disturb its functional nature, it does not have to be hung on the wall in order to motivate the drawing.

Now, at the beginning of the century, the artist gives the work of art to the surrounding everyday reality, places it in a space annexed by other objects. He uproots them, making from the work of art an object like those that surround us – but yet different. His thinking recalls the words of Baudrillard: There is no privileged object…

„The work of art forms its own space… The visions of an artist do not present but simulate – while manipulation refers to a world deprived of references, a world in which all references have died out. Art forms not only visions, but their meanings also – it "gives sense" and identity to something deprived of sense and identity.” 1

That which in Roland Schefferski’s work is a form of artistic gesture can at the same time be read as an expression of the humility of art. Art for the first time returns to life in such a way that it does not interfere with it, does not change it and does not try to do so, but rather takes its "own" space and waits until someone notices it. This is everyday reality "stamped" with the gesture of the artist, from which it is not possible to become free. This is an attitude of faith in either the receiver or the strength of art that speaks for itself.

Beata Frydryczak

1 Zygmunt Bauman, A few words about the art of meaning and the meaning of art (manuscript)